In the linguistically diverse landscapes that today’s European societies are becoming, grasping the linguistic repertoires of pupils can be quite a challenge. In light of this, a language passport is a useful tool to increase language awareness and to support the development of linguistically sensitive teaching (LST). The MARS language passport is an example made in Flanders.

Unravelling the language repertoires of the pupils in classroom is important, not only to enhance pupils’ and their teachers’ consciousness of the complexities of language use but also for schools to work on their multilingual policies. Dr Fauve De Backer, a member of our research centre in Flanders (Belgium), has developed – together with colleagues – a language passport within a larger study called Multilingualism As Reality at School (MARS).

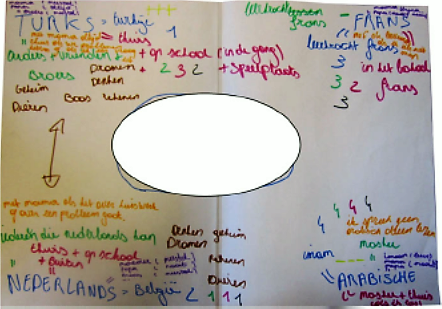

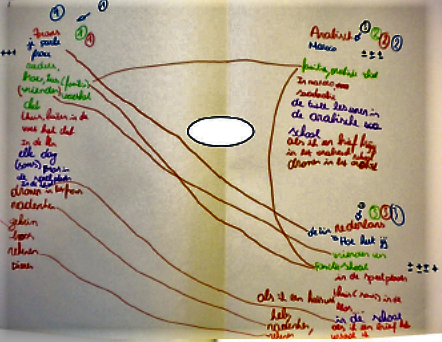

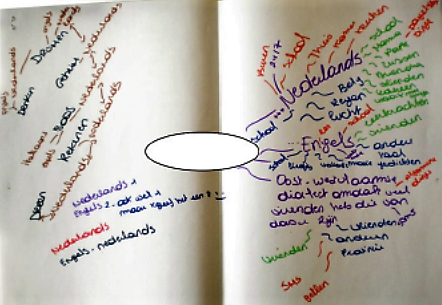

Construction of language passports can be an exciting classroom activity. This is like language portraits, where pupils paint their languages in different colours on a body silhouette. The MARS language passport is a written report structured as a mind map. This allows persons to present a clear overview of the languages in their repertoire: what languages they know, when and how they use them, how they feel about them, what the classroom community as a whole looks like. The MARS team collected data in 12 schools from 100 pupils in primary and secondary education who participated in focus groups. The aim of the focus groups was to gain insight into the linguistic repertoires and the dynamic and multileveled behaviours regarding pupils’ language use.

A first result of the study was that language passports showed the unconscious processes and practices underlying the use of linguistic repertoires. They demonstrated the individual variability and complexity of pupils’ linguistic repertoires. The passports captured multiple ‘types’ of languages used by pupils, including home languages, foreign languages learned in school and dialects, but also practices such as translanguaging. Multilingual pupils did not only use Dutch, the language of schooling, with people from school. Nor did they use only their home languages with people outside school (friends, parents, sisters/brothers). Dutch was used most often for calculating and thinking. This is not surprising, since it is the language of schooling. Home languages were more often used for “emotional” functions such as dreaming or telling secrets.

Pupils switched automatically and mostly unconsciously between languages. Not only when moving between different persons but also when communicating with one person. Despite such switching being a normal thing among multilingual speakers, the fear that this would be an impediment of their learning of the language of schooling was very apparent within the group discussions. Another interesting finding was that native Flemish pupils were multilingual as well, despite them often being regarded as “monolingual”.

All in all, language passports are an interesting activity for the entire class. They can be used for multiple purposes.

First, they can be helpful as a didactic tool, which includes the development of additional classroom activities. The passports depict the diversity and complexity in pupils’ language repertoires, they are one means by which pupils can be made aware of the unconscious processes underlying their choice of languages, they provide both teachers and pupils with new insights into their (own) language use, they are an accessible and easily adaptable way to discuss linguistic/cultural diversities in classroom, and they are a way to invite/accept home languages at school. Second, the passports can also be used to inform a whole-school multilingual policy. They give schools a greater understanding of their population while enabling them to adjust their policy and support for multilingual students. Third, the language passports can be used as a research tool as in school-based action research.

The MARS language passport was originally developed in Dutch. An English translation is in the making so not yet available online.

Written by Sven Sierens, Piet Van Avermaet & Wendelien Vantieghem

Ghent University, Belgium