How can we work towards a local language-and-education policy aimed at making teachers more linguistically sensitive? Researchers from Ghent University share their experiences and insights of what this means in the context of the city of Ghent.

Linguistic diversity and immigration in the Flemish region

Teachers in Flanders (the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium) are ever more faced with the question of how to address the needs of linguistically diverse student populations. These students usually have a poor immigrant background. They often speak home languages that have low prestige in society (Turkish, Berber, Arabic, etc.). The continued use of such languages is seen as an obstacle to learning the language of schooling (Dutch) and to school success. A territorial monolingual policy is strictly maintained in formal public spaces in Belgium, including Flanders. In Flemish education, this means that Dutch is the only officially permitted language of instruction.

The return of assimilation

Things took a promising start in the 1970s with the setting up of small-scale education projects showing a marginal openness towards inclusion of immigrant languages in the school curriculum. Towards the turn of the century, a shift towards assimilation took place in the political discourse. Admittedly, the dominant pedagogical practice in mainstream schools has throughout the years remained one of linguistic/cultural assimilation. This was worded in sugarcoating terms such as “integration”, “mutual respect” or “celebration”. From 2000 onwards, policy-makers began to state openly again that the mastery of the dominant school language is the sole key to school success of minority students.

Since then, a policy of more stringent linguistic assimilation is consistently put forward as the main solution for narrowing the persistent achievement gap between immigrant and non-immigrant students. Monolingualism is expressly promoted in terms of social equity. The suggestion is that the use of immigrant home languages at school is a cause of school failure and that (more) multilingualism will, in fact, increase social inequality in education. How else can we explain the statement of a former education minister that “multilingualism leads to zerolingualism”?

A linguistic turn at grassroots level

Fortunate for us as researchers and teacher trainers at Ghent University, the dynamics of language policies and practices are not that black and white at the local level. Dutch-only beliefs and practices imposed from the top down may still prevail. Yet from the bottom up innovative multilingual pedagogies do arise, too. Teachers and teacher educators try out alternative strategies in their day-to-day practices to overcome the gap between the monolingual mindset on the one hand and the multilingual realities of schools on the other. There is an emerging awareness that a Dutch-only language approach has its limits as a “one-size-fits-all” model for combatting social disparities in educational performance.

An emerging multilingual mindset

That among some educational practitioners the idea to change tack emerges as a spontaneous movement is plausible. Despite the fact that for decades now most mainstream schools have held on to a monolingual pedagogy, the existing achievement gap is still not substantially reduced. It’s true that all teachers consider “language” as an important lever to improve academic learning in immigrant/minority students. But instead of practicing this from a monolingual mindset, teachers may adopt a multilingual mindset. Teachers acknowledge then that students’ language repertoires contain multiple languages and varieties. These diverse repertoires are seen as a resource that can be capitalised upon in teaching and learning new languages and contents. In short, the focus shifts from the language to be learned to the already acquired linguistic multicompetence of the learners in building new knowledge in powerful learning environments.

Ghent: a turning point

Although teachers in Flemish urban schools show growing interest in this emergent “linguistic turn”, political support still lags behind. Yet not so in the city of Ghent. In 2006, a unique turn in local policy-making led first to the implementation of the five-year “Home Language in Education” project (2008–2013) in a number of primary schools. Its primary aim was to foster immigrant children’s positive attitudes, well-being and cognitive learning through the raising of language awareness and the didactic use of their home languages in mainstream class. The project aspired to help teachers become more linguistically sensitive and find ways to create linguistically inclusive learning environments where multiple languages can become valuable resources for academic learning across all subjects. We as researchers from Ghent University (with colleagues from the University of Leuven) carried out the evaluation study accompanying this project.

The project’s experiences heralded a positive change in the local educational policy concerning language use at school. For instance, children are allowed from now on to speak their home languages outside the classroom and are not frowned upon for doing this. Our local pioneering study was followed by a number of large-scale longitudinal studies on multilingualism in education. The local authorities in Ghent also created the Ghent Education Centre, which aims to support, connect and inspire children and young people, parents, educational professionals and their partners. One of the key themes addressed by this centre is diversity and multilingualism, making it our privileged local education partner in Listiac.

Change through collaboration and communication

Our experiences with projects in which we collaborated with key stakeholders (teachers, school administrators, school advisors, teacher educators, policy-makers, public servants), each having their own needs and interests, has given some understanding of how “change” in education, its guiding policies included, comes about. What we have learned is that such change is far from a straightforward journey. It’s a never-ending story that comes with ups and downs, with doubts and dilemma’s, and it depends on good and bad luck as well. We experienced a number of “critical incidents” in the internal and external communication of our projects. This includes inside talks with responsible politicians, professional development of practitioners, and public and social media. The communication of research to “outsiders” is a tricky business. All the more when a project shows mixed results, and positive developments cannot be demonstrated across the board. In fact, non-believing politicians and public communicators use their positions of power to jump on this. They magnify negative results (see, it doesn’t work) and frame positive results as the work of biased researchers driven by a multilingual ideology.

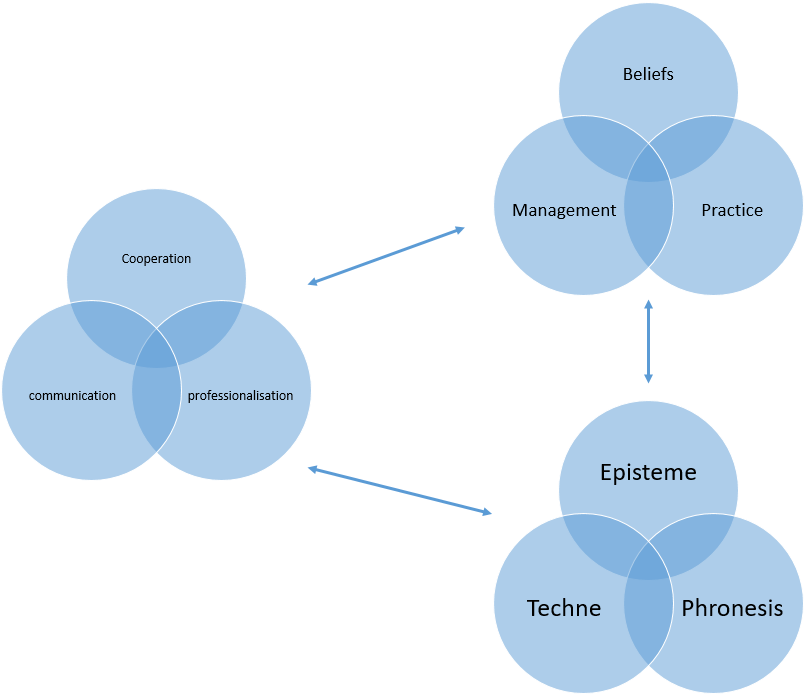

Advocacy for change: a model

To bring about the desired change, various factors are interacting with each other in a complex and dynamic way. We have brought together these factors in a model, which is visualised in the accompanying figure. It contains three parts, each showing three overlapping circles. The first part refers to type of professional interaction (communication, cooperation, professional development), the second one to factors influencing language policy (beliefs, management, practice), and the third one to scientific ways of thinking (episteme, techne, phronesis). The two first parts speak for themselves but the third one needs some explanation. Episteme refers to what is rational and universal in science; techne refers to the applied sciences, to art, craft and practice; phronesis has to do mainly with values and ethics.

Advocacy for multilingualism in education

Advocacy for multilingualism in education is not only dynamic and complex, it’s also time-consuming, intensive, messy and self-reflexive. It’s more than feeding research findings to practitioners, politicians and the media. By necessity, change in policy goes hand in hand with change in practice. Teachers and teacher educators can certainly be convinced of changing their everyday practice by supporting them with valid data and well-designed good practices that are embedded in tools used in their professional development. Examples of digital tools that we co-developed in recent years are two websites. The first website https://metrotaal.be assists primary school teachers and counsellors in their developing a language-inclusive school and classroom policy. The second one https://meertaligheid.be disseminates research-informed information about multilingualism to professionals working with linguistically diverse groups.

Lessons for advocacy of multilingual policies in education

University-based researchers and teacher educators who advocate more multilingualism in education need to show active engagement in bringing about a sustainable change in existing language-and-educating policies. In our experience the following conditions are crucial:

- Ethically-informed, solid, balanced and valid research data

- Intensive and sustainable on-site cooperation and engagement with a wide range of actors: teachers, school administrators, school advisory services, teacher educators and NGO’s

- Intensive on-site training and coaching of educational practitioners using research-based tools

- Proactive engagement with media coverage and debate

- Intensive long-term interaction with policy-makers instead of a confrontational ideological debate

- (Re)framing the discourses of our research and findings

But above all: accept that change of language-and-education policies is a long and winding road, a never-ending story.

Written by Sven Sierens and Piet Van Avermaet

Ghent University