By bringing native speakers of a given target language into the classroom, students have the opportunity to experience a myriad of positive language and cultural benefits, such as precise phonetic instruction, cultural input, and the sociolinguistic insight that comes with interacting with one’s mother tongue from a young age. Despite these positive elements, one problem often arises when the language teacher is not yet proficient in the language of the country in which they are teaching. How can they help to bridge the understanding gap when the students may be at a beginner level, or when certain language explanations are needed?

Once technique that has proved very useful was that of a language “helper.” As an American teaching French, and with some limited language skills in Lithuanian, I was faced with many language-related challenges when I took on teaching beginner French at a local elementary school in Kaunas, Lithuania. I felt that using a monolingual, French-only approach would be a recipe for frustration and chaos, as many of the students had never studied French before, and their own metalinguistic Lithuanian skills were still in the process of development.

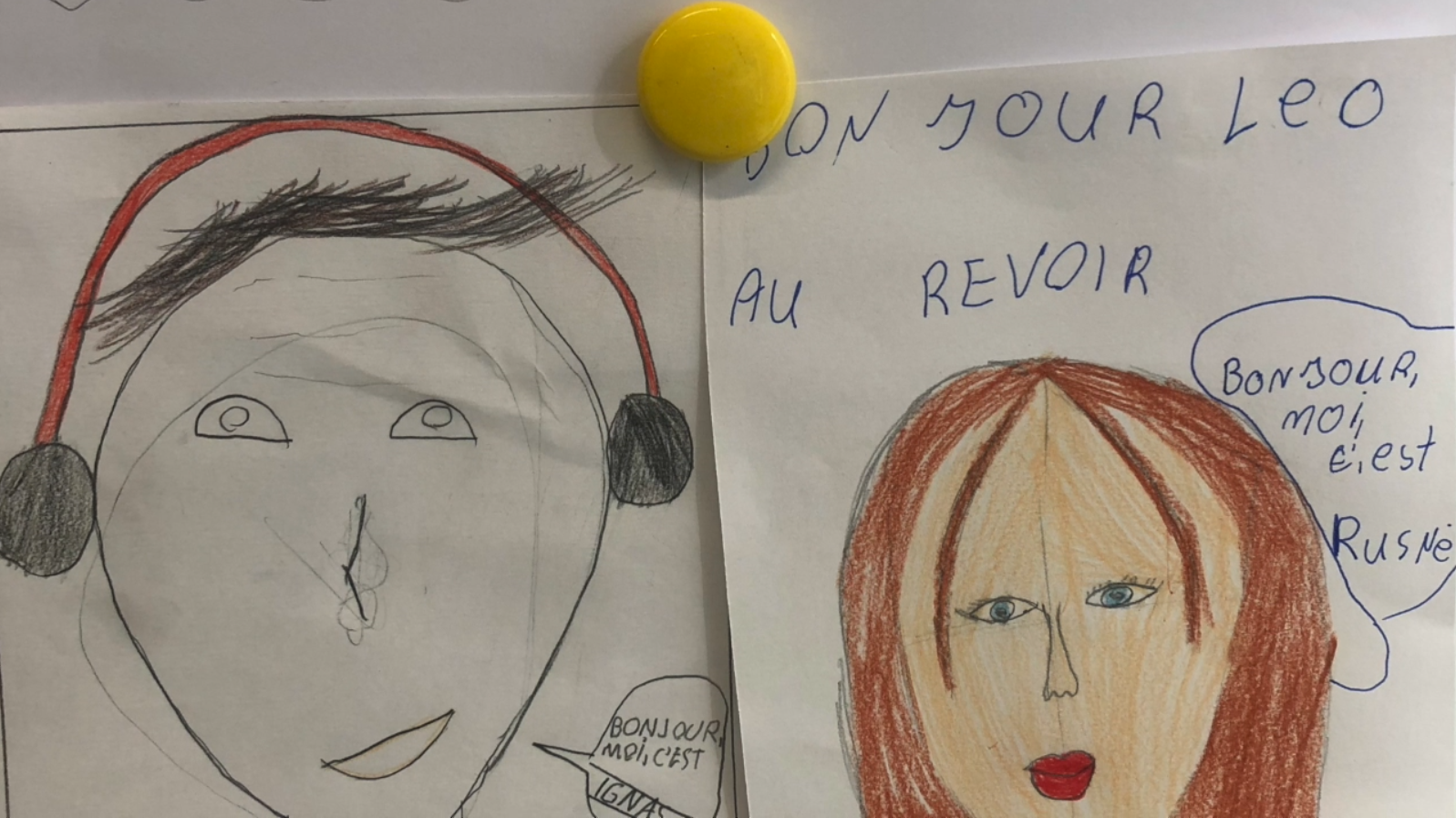

With this in mind, the first day of class, I asked if any of the students liked speaking English and would be willing to be my “special assistant” who could help me explain the class directions (“draw a picture of yourself”; “throw the ball to the person next to you”) and the occasional unknown word. To my surprise, several students were interested, and after choosing one, I promised the others that they could “have a turn” at being the assistant next time. As time passed, I found that adding realia such as a microphone, a name tag, and other accessories made the “assistant” position even more appealing, and it also helped to foster a sense of community in the classroom. The assistants were able to exercise a leadership role, with the other students felt that their native language was being respected and catered to, even when their teacher did not yet speak it herself. This technique also allowed us to make comparisons between French, English, and Lithuanian, and gave each language the opportunity to be promoted on the same level.

I even showed them clips from UN meetings with live interpretation, to perhaps inspire in some of the assistants the desire to continue in the field of interpretation and translation, and to demonstrate the power of plurilingualism outside of the classroom. After just a few weeks, even the most timid students were trying their hand at “assisting” in both French and English, and the visible confidence they gained was a testament to their persistence and sense of ease in the classroom environment we had created together.

As time progressed, the students grew more and more comfortable in French, and the need for our assistant was less prominent. However, the students knew they were always welcome to ask questions in any language, and that together, we would collaborate to find an answer.

See the process in the video below:

Written by Taylor Smith

Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania